In 1951, delegates of the Federation of Victorian Film Societies to the Australian Council of Film Societies Convention at Newport, a Sydney suburb, invited the Council to hold its next convention in Victoria; the Council accepted and it was agreed to arrange a conference towards the end of January, 1962.

After many locations had been investigated, the mountain resort of Olinda was selected and it was decided to expand the convention into a miniature festival. Invitations were issued to all who were interested and several guest houses were booked for the eighty people expected to be accommodated over the Australia Day week-end. The Commonwealth Government agreed to announce the Commonwealth Jubilee Film Competitions Awards at Olinda; five halls and an outdoor theatre for 36mm. projection were rigged up and the Army co-operated by connecting the guest houses and halls by special telephone. Thus Olinda became the birthplace of the Melbourne Film Festival.

The atmosphere at Olinda was completely informal and it was even expected that the shows would run into the early hours of the morning. By present day standards the fare was modest, the highlights being Cocteau's 'Beauty and the Beast', Flaherty's 'Louisiana Story' and a new Chinese feature film. Several extracts from early Australian films were shown in addition to some fifty-odd shorts which were given their Victorian premieres.

The Olinda Festival attracted about five times as many people as the Federation initially expected and presented problems as well as opportunities in planning for the future. If the Festival was to develop it was necessary that a large theatre, more centrally situated, be found. The only practical location available in early 1953 was the Melbourne Exhibition Building, and at Easter that year the Second Festival screened Rossellini's 'Germany Year Zero', Flaherty's 'Moana', Rotha's 'No Resting Place', Hoellering's 'Murder In The Cathedral', with a number of other features and many short subjects.

The Exhibition Building was never designed for showing motion pictures and the bad acoustics of the halls spoilt the presentation of many of the films. Membership response fell below that anticipated, and, coupled with the expense of projection equipment, the result was that the '53 Festival was financially ruinous. Undeterred by these setbacks, the organisers found a home for the Festival in 1954 at the Union Theatre 'at the University.

Expanded to three weeks, the '54- Festival included 'Martin Luther', 'The Back Of Beyond', 'Man Of Aran', 'World Without End' and a number of Italian and French films including 'Jour De Fete', 'Sunday In August', 'Une Partie De Campagne', 'Sous Les Toits De Paris' and 'The Golden Coach'.

In 1955, the Festival, developing the pattern of '54, grew to maturity. Fewer "classics'' and documentaries were shown in the major programmes, but the emphasis was still on Italian ('Umberto D', 'Miracle In Milan') and French ('Les Jeux Interdits', 'Orphee', 'Pepe Le Moko') films. But '55 really became famous for introducing the first Japanese film, 'Gate Of Hell', into Australia.

In 1956, the Festival became more international, opening with Orson Welles' Moroccan 'Othello', followed by the German 'The Eats', Brazilian 'O'Cangaceiro', British 'Animal Farm', French ‘Olivia', Polish 'Five Boys From Barska Street', Japanese 'Seven Samurai', Yugoslav-Austrian 'The Last Bridge', Russian 'Childhood of Maxim Gorki', Czech 'The Proud Princess', Indian 'Two Acres of Land', Chinese 'Liang Shan-Po'. Even the "classics", which had become a pattern of the Festivals, went "international" with the Swedish 'Gosta Berling' and the German 'Three-Penny Opera'.

The '57 Festival continued to maintain the cosmopolitan outlook, the motto being "110 films from 31 countries". For the first time Greece ('A Girl In Black' and 'Windfall In Athens'), Israel ('Hill 24 Doesn't Answer') and Bulgaria ('It Happened On The Street') were represented. Youtkevitch's 'Othello' and Donskoi's 'Mother' were shown along with other notable entries: 'Frenzy', 'Les Orgueilleux', 'On The Bowery', 'Jan Hus', 'The Titan' and 'I Vitelloni'. Other highlights of a successful year were the exhibition in the National Gallery of outstanding Polish posters, the introduction of the British "free cinema"" pro- grammes into Australia, and the presentation of the first part of Satyajit Bay's magnificent Bengali trilogy, 'Pather Panchali'.

With the recognition of the Festival by the International Federation of Film Producers' Association, the 1958 event was able to present some new productions from France ('He Who Must Die'), Germany ('The Devil's General') and America ('Sweet Smell Of Success', 'Paths Of Glory'). Altogether 130 films were shown including the features 'Friends For Life', 'Kanal', 'Don Quixote', 'Albert Schweitzer', 'Every Day Except Christmas', 'Professor Hannibal', 'Farrebique', 'Against All' and 'A Glass Of Beer'. Asia was represented with the Korean 'Wedding Day', Japanese 'Samurai', Chinese 'New Year Sacrifice', 'Aparajito', part two of Ray's trilogy. Experimental films were well to the fore with 'Dreams That Money Can Buy', 'Blood Of A Poet', '8x8' and 'The Pleasure Garden'.

The 1959 Festival included films from new sources such as Spain ('Calle Mayor'), Norway ('Nine Lives') and the Philippines ('Badjao'). For the first time in several years no features from Italy or France were shown, hut the Festival was able to show some world-famous productions such as the Mexican 'Los Olvidados', Russian 'Ivan The Terrible—part II,' Danish 'Day Of Wrath' and Japanese 'The Harp Of Burma'. Other films from a memorable year were 'The Horse's Mouth', 'Throne Of Blood', 'The Captain From Koepenick', 'Eva Wants To Sleep', 'Wolftrap', 'Anna', A Matter Of Dignity', 'At Midnight', 'The House I Live In', 'Terminus Love', and the celebrated 'Rose Marie'.

Continuing with its plan to explore new territories, the 1960 Festival selected the Singalese 'Rekava', Tunisian 'Goha', Dutch 'Fanfare', and Finnish 'Sven Dufva'. Older film-producing countries were re-explored for the work of the independents— the British 'We Are The Lambeth Boys', the French 'Hiroshima Mon Amour', the American 'Savage Eye'—but the established directors were present with Kurosawa's 'Living', Rossellini's 'General Della Rovere', Ray's 'World Of Apu', Weiss' 'Appassionata'. Notable films from Poland ('The Last Day Of Summer'), Russia ('Destiny Of A Man'), Hungary ('House Under The Rocks') and Bulgaria ('Stars'), together with two works from the pen of Chayefsky—'Middle Of The Night' and 'The Goddess'—were amongst the other features screened.

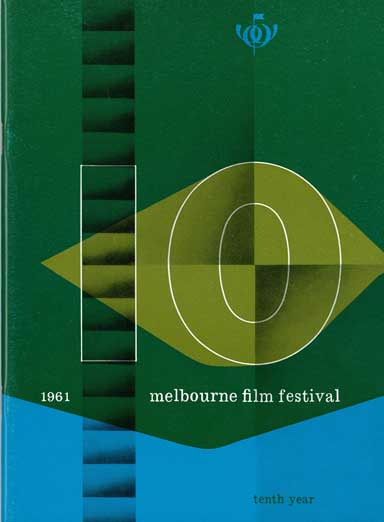

Members of the Tenth Melbourne Festival will find the wide array of films to be shown described in this programme booklet. Recent films by Bunuel, Heifits, Pyriev, Ophuls, Ray, and Ranody are arranged along with new films from Spanish countries, new features from Holland, Denmark and Germany.

A Festival can be no better than the films produced during the preceding year or so, and it should reflect the state of world cinema during the immediate past. If the previous year was a triumph for the young French cinema (as shown in the 1960 Festival by 'Hiroshima Mon Amour') then last year was a victory for Italy with films of the calibre of L'Avventura', 'Rocco E i Suoi Fratelli' or 'Morte Di Un Amico'. But these films are not available to us.

It is not always possible for a non-commercial film organisation, such as the Melbourne Festival, to obtain any film that it would like to screen, and these restrictions do not apply only to the older film-producing countries such as America, Britain, France or Italy. Since the First Melbourne Festival was arranged in 1952, the number of feature films — apart from those of British or American origin — imported into Australia has more than quadrupled, and the number of cinemas showing this type of production has also increased.

In 1952 it was a rare thing for a "continental" cinema to show any film not of Italian or French make; nowadays it is commonplace to see Swedish, German, Polish, Spanish, Hungarian, Greek, Czech, Russian and Indian films in our theatres.

We in the Festival feel that we have been partly responsible for this widening of cinematic taste and we rejoice that our theatre managers now show films from countries that they would not have considered at the time of the first Melbourne Festival. If, this year, we show films from Argentina, Denmark, China, Holland, and Mexico, perhaps by 1971, our cinemas will have extended their interest to these countries. Yet we regard it as part of our function to continue this exploration of unknown sources, and hope that, before long, we will also be able to show Australian feature films of world calibre.

Introduction taken from the 1961 official guide